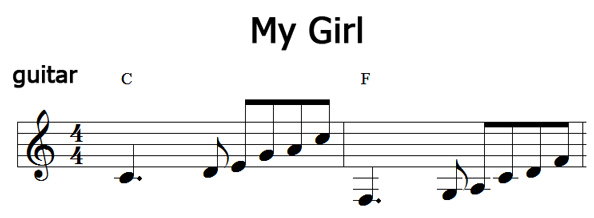

My Girl

You already know the pentatonic scale, having heard it all your life. For example, you’ve probably heard the Temptations song My Girl many times. Smokey Robinson wrote the song, but it was Funk Brothers guitarist Robert White who conceived of and played the classic guitar riff (clip):

As you can see, this is the C major pentatonic scale followed by the F major pentatonic scale. Instant rock history.

The Way It Is

Let’s look at some examples of using add2 chords. Here’s my transcription of the piano riff from Bruce Hornsby’s The Way It Is (clip). I think it was these few notes, all based on add2 chords, that first made everybody take notice of Bruce Hornsby.

There’s not too much to say about this example. The second chord is Fmaj9, but I’ve named it Fmaj7add2 here to draw attention to its add2 essence. Maybe one day you’ll get famous playing your own riffs based on add2 chords.

Dr. Wu

I saw Steely Dan a couple of years ago in Boston on Internet Request Night, and it was apparently the first time they ever played Dr. Wu live. Awesome. I scanned this transcription I made quite a few years ago because I can’t seem to find the file.

The introduction (clip) is a little master class on mu (add2) chords. The first chord, which I called D/E, is the mu chord Dadd2 played with E (the 2) in the bass, resulting in a cool slash-chord sound that’s very characteristic of Steely Dan. Since the chord is Dadd2 hopefully by now you’re thinking D major pentatonic.

Next come some tinkly high notes immediately repeated an octave lower. If the chord was G, this would be the country third. But we’re still holding the pedal letting the D/E ring, so we should think of this as D6. Adding the sixth (the B) to the chord makes this a D69 -- all the notes in D pentatonic.

Next comes C/F. You might also call this Fmaj9no3. You see the 9 in the chord, so you could be thinking about F major pentatcall onic and Fsus2. C/F is Fsus2 plus the major seventh (E), So you could think of C/F as Fmaj7sus2. If you had to solo over this chord, C pentatonic should work nicely. F pentatonic picks up the A (not in the chord) and loses the E in the chord, so is less ideal. Similarly G/C is Cmaj9no3 or Cmaj7sus2.

The last chord of the introduction shown here (there’s a bit more I cut off) I called Em(4), but it’s perhaps more properly notated as Em74. Em74 you might recognize from above as the chord name for all the notes in the Em pentatonic scale. In this case the fifth, B, is omitted from the chord, giving the Astacked4/E voicing we see. If we rearrange the stacked4 as a sus2, we see it’s Gsus2, which implies G major pentatonic (there’s no harm playing the third, B) which of course has the same notes as the relative minor, E minor pentatonic.

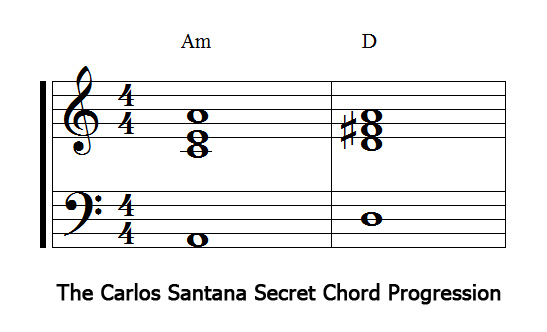

The Carlos Santana Secret Chord Progression

Am D (picture above totally unnecessary) is the Carlos Santana Secret Chord Progression. I think the name originated with Zappa -- that’s where I got it, anyway. You not only hear it in Santana (Evil Ways, Oye Como Va) but in lots of other classic rock as well, like Pink Floyd’s Breathe and Great Gig in the Sky, Neil Young’s Down By the River, Stevie Wonder’s I Wish and many others. One of my favorites is Mark-Almond’s The City, a particularly pure example of the jam that repeats this progression for eight minutes. Like many basic progressions, in practice the chords often appear with a few more thirds stacked up, for example Am7 D9.

It feels like it’s in A minor, and indeed, A minor pentatonic and A blues work just great over this. Even though the progression uses a major chord for the IV chord (usually a minor key would use the minor chord for the four), the minor pentatonic doesn’t have any preference for a minor sixth or a major sixth, the sixth being the third of the four chord.

The usual advice for this progression (and indeed many minor key tunes where the four chord is a major chord) is to jam this in the Dorian mode, A Dorian. I personally find modes confusing because they’re yet another way of counting or naming small numbers in music that you have to remember: Ionian=1, Dorian=2, and so on. Then you have to remember what the number means: for example A Dorian means the major scale where A is the second (the 2), i.e. G major. So the advice to play A Dorian means play notes from G major, which is A minor pentatonic plus the b and the f#.

You could also play A minor pentatonic over the Am chord and D major pentatonic over the D chord. That works great too. Not coincidentally, the union of the A minor pentatonic and D major pentatonic (taking notes from each) is G major, also know as A Dorian.

We got at this obliquely, talking about minor keys and modes. More directly, you can form a major scale from the union of the major pentatonics of the fourth and fifth scale tones. So, G major is the union of C pentatonic and D pentatonic. (You could add in G pentatonic too, but that doesn’t add any new notes.) You can understand why this works by going back to the circle of fifths (see above).

Bloody Well Right

The electric piano introduction to the Supertramp hit Bloody Well Right has a very blues scale sound to it (clip). I deliberately didn’t label the chords for the left hand part pictured above, but they’re Ab and Bb in the intro. I’ve seen a similar progression later in the song notated as Fm7/Bb Bb, which is a variation on the Santana secret chord progression with the 4th (Bb) in the bass in both chords.

From the chords, you might reasonably expect the right hand to use Ab bluesy (F blues), Bb bluesy (G blues) or Eb bluesy (C blues). The Eb comes from the fact that these are the IV and V chords in Eb major. In fact, the intro switches between all three of these scales.

Somewhat surprisingly, the right hand is mostly Bb bluesy (G blues). It’s an unusual choice that hints at the Bb bass pedal tone to come. The intro does slip into Ab bluesy (F blues) for a few notes, which is what I’d probably play over the Santana-like Fm7 Bb. But it quickly goes back to G blues. C blues crops up too a bit later.

One way to determine which blues scale the player has in mind is to focus on the three note chromatic runs in the solo. The pentatonic scale has no semitone intervals, so the half-step motion gives a strong hint to what the blue note is, and thus what blues scale it is. When you hear a run “c c# d” there’s a strong possibility that the blue note is c# and thus the scale is G blues. Similarly, when you hear “f f# g” the blue note is f# so the scale is C blues. The (non-chromatic) Ab note you hear (as in “f Ab Bb”) indicates the solo has ventured into F blues (or at least F minor pentatonic) at that point.

Next: Can You Organize All That?